Born in early morning under birch tree, born in snow painted red with her mother's spill, she had only ever known barren earth, packed hard and frozen underpaw.

Everything around her: gray, black, white—high contrast—sharp as instinct, sharp as smell of elks' blood cutting through cold air like arrow, like bullet, cutting like hunger. This land was a jagged place, and she hardened like a diamond pressed between its palms.

Run. Grow big and run. Run with them, the seven whose fur she buries her muzzle in to sleep—if sleep came. The whole world rushing, always rushing toward her. Even when she sleeps, every sound the forest makes an omen, every hot breath from a jackrabbit's nose a calling: Run. Catch. Thrash. Feed. All of it, all of it, every day forever until death closes its mouth over her eyes like a dream, the air stops coming, body grows stiff like earth. Then, more life, growth, death, over and over—and that is what it was to be a wolf.

Sometimes she grew restless, more restless than the others, left them sleeping in dark, twilight gray at the mouth of the cave as she did what she should never do—go off alone.

When she was alone, the world was no longer so fast to pass her by, and she could stop and turn over a cake of packed snow with her nose, smell every paw, hoof, and foot that had trod there and know, for a moment, what History was, and that foolish curiosity that had led wolves before her to early rot.

Each time she went, she tried to go a little further than the time before, always following the river downstream so as to find her way home more easily. The river every day growing murkier with ash, with sewage, dead fish floating to the surface of the thin ice, preserved beneath on their sides with one wide-staring eye, mouths frozen in perpetual cry. They had swallowed so much sickness as to blacken their scales, eaten from the inside out, tar bursting from gills.

White men came for gold, would do anything for gold, would die in avalanche for gold, freeze and starve to death for gold. White men came and cut living trees, cleared the way for their boomtowns. It was a mean place made meaner by blighted hopes, White men promised plenty and finding famine. White men despairing in the isolated Yukon, White men reaping Hell for their greed. They forced the native Hän downstream, killed the native Hän for gold, spread their sickness to the native Hän's men, women, children, and to the fish they relied upon.

Dawson City was the hub from which all disease flowed. Its rowdy patrons were grizzled men with blackened hands and women weighed down by the mud on their long skirts. Plagued by fires, its ruddy buildings sat slanted atop the hard ground; once collapsed in ash, they simply brushed the waste into the water with the piss and shit, to be sent downriver to the reserve the Hän had been sequestered to.

Parties of men would lash their guns to their backs and traverse the riverbank daily, scouting for wayward Hän people.

She kept her nose to the ground, pushing the snow so her advancement along the riverbank was marked by a playful trail of rivulets. She heard the voices first, deep and angry. her ears pricked up, pupils dilating, frozen.

A loud crack whipped the air, setting the birds in the trees to flight, thin branches shuddering, snow pelting the ground as the whole world seemed to lurch. Blood on snow, hot like fever; the Hän man's body taken under by a death roll, by buckshot torn through his chest ragged as alligator maw.

She ran blindly into the shelter of the trees, threading through naked bramble, felt it clawing at her fur and pulling it away as she persisted. In her mind's eye, the sound of the gun, the pulse of the Hän man's heart and the startled look in his eye, same look as moose's eye, same fear, no animal more or less inclined to mortal terror. She ran until she could no longer hear voice nor boot tread, ran until she reached a clearing encircled by birch trees, smelling of home, smelling of her birth. She collapsed, panting, mind whirling dizzily and always returning to the eye, that dying eye and the rust-colored barrel of the White man's weapon.

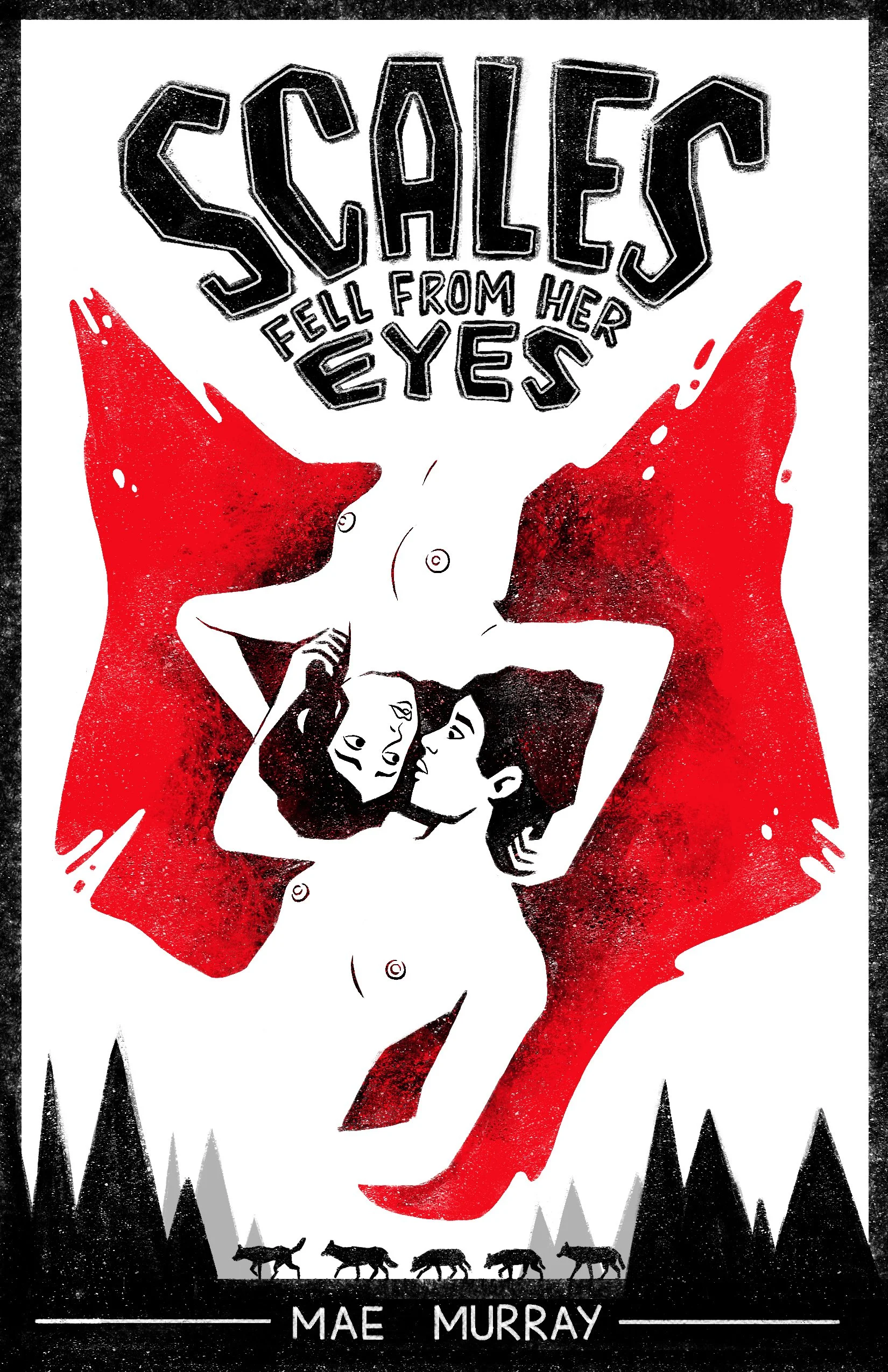

Her back arched, hind legs bracing in the snow as her tail stiffened. She whined, tried to stifle it, feared being heard, but pain came now in waves, came like birthing pains when bitches' bodies heaved with pups. The knobby spines of her vertebrae pierced her skin, blood blooming in her thick fur, bone reaching to the sky, a row of ruby flowers stretching toward the sun. Beneath it, another body growing in like a tooth, its tanned skin silky, awash with slick innards as wolf skin and bone peeled away. Fruiting body, sleek and ripened body, smell of metal and the cold like she'd never felt it before. Her muzzle dropped away, her flesh great gobs of meat hanging at her throat like a wattle before sloughing off her new breasts.

She cried out, a human howl, air cold and scathing in her esophagus. Her body stretched up and out of her old skin, trembling hands clenching snow to pull her way from its ichor. Legs kicked, tangled in the meat and skin, fighting her way out of its net until she lay bare in the cold on her back, her arms crossed over her chest and knees drawn over her abdomen. Had she been inside all along, a fetal spirit folded inside a wolf's stomach since birth? She could not know, could not reason with the nature of what is.

The cloak of fur hung heavy about her shoulders, skin awash with the proof of birth. She shivered within it, her bare feet curled in the snow, the pain working its way into their soles and climbing up her legs until she felt nothing at all from the waist down. Her breathing was a sick, rasping thing, her dark hair, slickened by blood, catching in the low-hanging fingers of trees.

She smelled it first: the pyre of Dawson City burning with tobacco and smoke from elks' meat trapped in metal ovens. Her mouth watered, and she followed the scent to the mean city, the smokey flavor of the air increasingly sharpened by piles of horse manure stomped into the path.

Harriet's husband had died in the avalanche on the Chilkoot Trail, so she had continued the journey to Dawson City alone. There, the men called her Harry, and she drank like the rest of them. To survive them she had to become just as rough and cruel in their company, and she joined them in their search for gold despite the bleak futility of it all. What else could she do, could any of them do? There would be no leaving this barren place—no scenario in which they did so with their pride intact—and the exodus would be just as treacherous as the pilgrimage.

Harry herself had lost two toes to frostbite after being buried in the snow some ways away from her smothered kin. Later, she amputated the blackened stumps herself using a crude pair of tin snips from her husband's tool belt. The night she cut them, like two swollen cigars, she did so in the saloon on a dare, a gruesome gamble by disillusioned louts; a gamble she had won, used the money to earn her supper for a fortnight.

Harry saw her from afar, this huddled creature with a cloak of fur, ambling through the cutting snowfall on its hind legs. Though she was good and liquored up from her customary evening at the saloon, her instinct to reach for the revolver at her belt was swift. She cocked the hammer back and advanced, careful steps in the snow now, every nerve in her body beaming with caution. A rather small, sickly bear, she thought—a starved thing that had lost its way—had followed the smell of smoked meat in vain hope of sating its hunger. The closer she drew, the smaller the bear appeared, until she found herself upon it and saw it wasn't a bear at all. It was a woman, naked but for the fur thrown over her head. Harry gasped.

"Christ!" she spat, pulling the fur from the woman to reveal her face, disoriented and pale against the backdrop of the black night sky. She threw the fur back around her shoulders, enveloping her in a tight embrace, guiding her with her body back toward her home just on the perimeter of Dawson City.

She kicked the door open and ushered the woman inside, immediately bringing her toward the fire, which still licked at a pot of hot stew consisting only of salt, water, potato, and elk.

"What were you doing out there?" she asked, her own body shivering next to the fire as she took the woman's feet in her hands and rubbed them; frozen solid, they felt, but curiously devoid of frostbite.

What language was this? She did not speak, did not know those strange syllables from soft lips, so unlike what she had known of wild mouths tinged with scent of meat and pine, tangled with ancient animal tongue. Those foreign sounds, wrought from breathing in cold and dust, wrought from surviving flu; this woman, this human creature, incomprehensible as silence.

Desire like peach pit stuck in throat. Desire like breath held in free fall. Harry's hands moved over the stranger's body with a cloth to scrub away the remnants of birth: blood, fluid, clinging membrane from a desiccated womb. The body was lithe and firm save for her breasts, which Harry's gaze lingered upon—the pertness of the nipples drawn from the cold. She released a long breath as the she-wolf's eyes followed her touch; color of honey, color of gold. Her desire tinged every brush of her thumb, skin melting into the softness of skin, and the stranger said and did nothing, neither movement nor speech, just shallow breathing from parted lips.

Harry's thoughts turned inward, to her late husband and the fool's errand of making the journey from California to Canada, from desert to desolate landscape to displace those already living there, to mine for resources that did not belong to them and, as far as she had seen, did not exist in the first place. Oh god, she had thought, making that fateful climb along the Chilkoot Trail. By that time she had been two months pregnant, certain the strain would cause her to lose the child. And it did, its barely conceived body lost under the snow where she'd miscarried it, several yards away from her dying husband.

She had been so angry then, angrier than ever before, this man driven by greed, her life heavy with his expectations—move from family and friends, bear my child—a son to lift and build and be desirous of riches and women, as all men should do and be.

Leaving the fetus in the snow from which she emerged, freezing, her hair crystallized into strands of ice hanging about her face like daggers, she dug in the snow, deep, deep, pried the Chilkoot map from her husband's pale blue hand, pulled his tool belt free, did not heed the twitching of his fingers—this man, her husband, abandoned to his death. She brushed the snow back over his quivering and terrified face, listening until the rattle of his breathing stilled.

And had he deserved it? She often wondered, and wondered now as she sat before her unexpected guest. Had she deserved to lose her child and walk this trail alone with the blood of it dried on her thighs? No, there was no deserving; the bad were rarely punished and the good always suffered, and every life leading always to the same place—a hollow death.

Her husband's life had only cost her two toes, had been worth less than that. Of all she had sacrificed, those two dead digits were the least of it, were only a manifestation of the black hatred in her heart, the withered desire and sinful inclinations she had been forced to suppress.

Remembering all this—remembering some girl from long ago, fair-skinned and freckled, the one with the mole on her inner thigh which she kissed and kissed again—she looked into the stranger's eyes, shifting closer as she ran a brush back through her matted, unclean hair. In the midst of all these memories and in the midst of her bitterness and pain, something inside her dislodged; a deluge of longing, of old hurts gone uncomforted and heady sensations too often untended. Harry rushed toward her, parted her mouth to drink in her spit as if to slake her own primal thirst.

Memory of running through brush thick with nesting doves, the beating of their wings against her fur as they thrashed their way into the sky, abandoning their eggs—that is what it was like to be touched. A frenzy, a shock at the pliancy of her skin under rough palms. Wolf fur felt of velvet, but the flesh was resilient, tough as bark, and the skin she wore now was malleable and unfortified.

Brush of lips across her throat, warm bloom in her abdomen, her trembling hands lingered at the woman's shoulders, slipped around her back; if she was her homeland, the line of her body was the river. Eyes wide, she explored.

The din of the Dawson City morning thrummed into Harry's consciousness, the groans of men recovering from drink and the stomp of horses' hooves as they doggedly moved in droves; their search for gold was a fruitless but vital routine, if only to say they had tried.

In the dim cabin, the fire had been reduced to embers and the untouched stew was tepid, had formed a film of solid elk fat over the top in the cold of the night. The stranger had gone and had taken Harry's clothes, she realized, leaving behind the untanned pelt.

The she-wolf had observed the curve of the human boot, had surmised how the human foot fit inside, had taken the human's threadbare clothes to insulate her vulnerable skin. Staggering through the snow, her arms wrapped around her shoulders, her breath was hot and heaving just as it had been the previous night.

Once, in her other body—which now seemed so alien—she had lost her footing on a steep, icy incline, had felt her body pitch forward so that her tail went up and over her head, her stomach listing into her throat as she yelped. Such was the feeling of what occurred between herself and the human stranger; a thrilling tremor that had worked its way to the bone, had seized her—wet like snow on fur, slick like fish scale—yes, had seized her at the confluence of humanity and primordial urge and had awakened a previously unattainable knowledge of sensation.

This was not heat as she'd known it, was not the scent and rough of animal rut, was not the knotting, painful thing that all wolves must do. It was something more than that, and she followed the river back downstream, intent on telling the others.

Her senses were not as sharp, nose could not make out the birch beneath which she had been born, but she did not need to smell what she could plainly see: there was the tree with the dead and broken limb, hanging like a jutting bone over the water, and there was the place her sister had drowned, fallen through the ice and silenced forever, and there, just beyond the trees, was home.

Her feet slipped in the snow in her scramble to the lip of rock that formed their shelter, making out her seven pack mates through the pines. She watched their tails flick and bristle, bodies springing up as their ears folded back. With no human language nor wolf tongue, she managed only a sound somewhere in-between, something wholly indecipherable to either species. She held out her hands to placate them.

Meat was life, hot like thick liquor burning down howling throat. A flurry of crimson-coated paws upset the ground, warmth of blood melting soil, making reddened clay of it which clung to dripping muzzle. Stench of body in throes of death, so many huffing mouths and peeled-back lips nosing in a frenzy of torn flesh and fabric.

Run. Catch. Thrash. Feed. All of it, all of it, every day forever until death closed its mouth over her eyes like a dream, the air stopped coming, body grew stiff like earth—and that is what it was to be a wolf.